Ending AIDS by 2030 means removing bottlenecks to care and treatment – but what causes them?By: Dr Jenny Renju, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The expansion in the provision of life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa over the past fifteen years has been an unprecedented achievement for public health, resulting in dramatic declines in HIV-related deaths and disease.

By 2015, just over half of the 10 million people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa were accessing ART, paving the way for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) to launch a bid to eliminate AIDS by 2030. This would require that 90% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) are diagnosed, 90% of those diagnosed then initiate ART, and 90% of those on ART adhere to their treatment sufficiently well as to achieve viral suppression.

This week, Paris is hosting the International AIDS Society conference. The event provides a further catalyst for rolling out policies to achieve the 90-90-90 targets, so now is a good time to take stock and examine how the most affected countries address the challenges in meeting them.

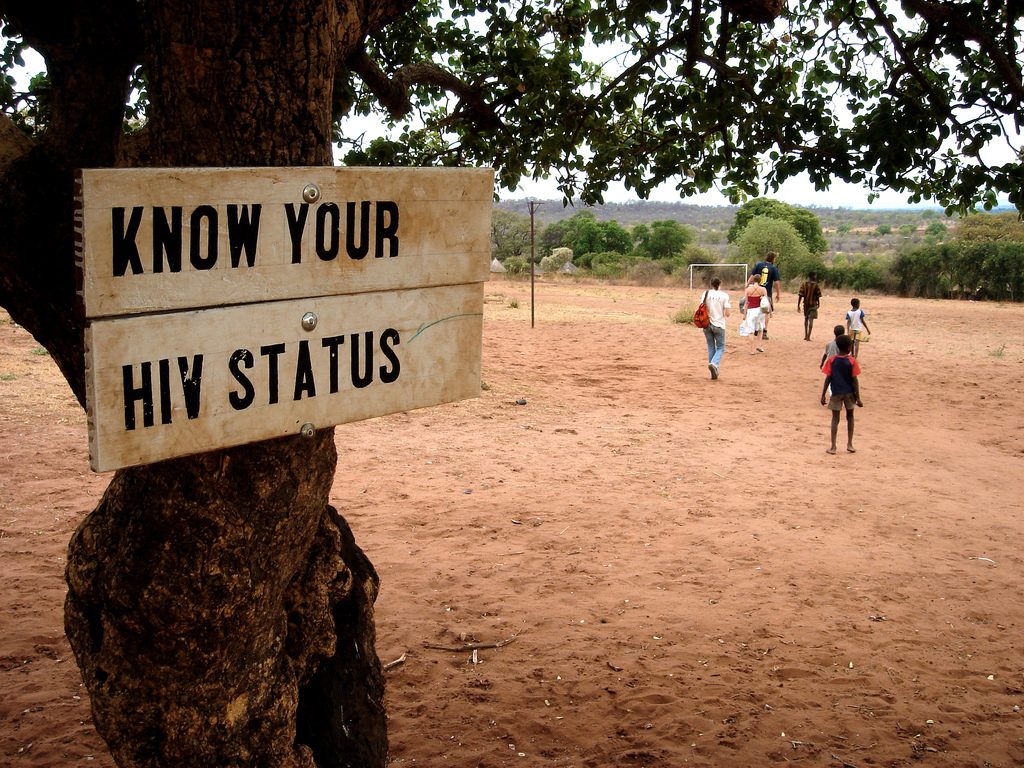

Making ART available for all PLHIV+ is a huge step forwards towards eliminating AIDS, but significant stumbling blocks remain. Many people do not feel ready or willing to undergo a HIV test, and those diagnosed may not feel able to take the daily drug regimens for the rest of their life. Understanding and addressing the reasons for existing barriers in HIV care and treatment is critical to achieving a future free of AIDS.

Contextual, social and health system factors influence the engagement of PLHIV with HIV care and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, but how? Our ‘Bottlenecks’ study published in the journal Sexually Transmitted Infections has provided crucial insight. Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the multi-country qualitative study examined the bottlenecks to HIV care and treatment at seven sites in six African countries; Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Uniquely we were able to draw on locally available census data linked to HIV clinic records. This meant we could identify and interview PLHIV with different HIV care and treatment histories, including those who had disengaged from the HIV care process and family members of PLHIV who had died. Such groups are notoriously difficult to include in qualitative studies. As a result, their voices and stories are often missing from accounts of HIV service use, resulting in policy recommendations that focus on those who face fewer challenges to HIV care engagement.

We found that interactions between patients and health workers, who are often desperately overworked and underpaid, had a huge influence on care seeking. In some cases, health workers believed themselves to be considering the patients’ best interests when using persuasive tactics to increase the number of patients undergoing HIV tests. Health providers, in an effort to achieve viral suppression, are also often failing to recognise the impact of debilitating side-effects that PLHIV endure on their engagement in HIV care.

Furthermore, we found that many PLHIV consult with alternative and traditional healers, although this was rarely accepted within the biomedical sector. Health workers must accept patients’ desires to access multiple channels in order to reduce the conflicts and confusions which culminate in bottlenecks.

Another major issue that affected engagement with HIV services across all settings related to couples’ relationships. For many, fear of blame, abandonment or abuse resulted in an unwillingness to disclose their HIV status to each other. Even among mutually disclosed couples there was little scope for them to attend appointments together, or to collect drugs for their partner if they were too busy themselves.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, despite improvements to HIV care services and over a decade of HIV care provision, stigma remains a persistent barrier, not only within couples but also within the community at large. This is undermining engagement with HIV diagnosis, care and treatment in all of our study settings.

As we move towards universal ART, greater acknowledgement of these issues is required. But these are exciting times – there are several bold and imaginative approaches to address these concerns on the horizon.

Self-testing for HIV is enabling many underserved groups to learn their HIV status, and continued decentralization of care and task-shifting to lay and peer health workers is breaking down barriers to accessing treatment. Patient-centred care that recognises different patients have different needs is beginning to take precedence over the previous one-size-fits all approaches that we have seen until now. New family-centered models of care are also being proposed to enable PLHIV to not only test together, but to also collect drugs for themselves and their partners.

These approaches must be tried, tested, revised and scaled-up in order to unblock the persistent bottlenecks to HIV care and treatment. Only then the ambitious goal of AIDS elimination by 2030 can be reached.